Urban planning tools in a multicultural city – Towards peaceful coexistence

Emma Savela

As social debate and the political climate become more polarised, the role of urban planning in enabling different groups of people to live together is growing. Urban planning can create places that enable coexistence and encounters, or restrict them, reminds Emma Savela in her text for the series Everyone's Architecture.

In recent decades, urban development has been influenced by two major social themes in particular: rapid urbanisation and increasing immigration. In Finland, immigration is still often discussed as a new phenomenon, and Finns have even been referred to as an exceptionally homogeneous people.

However, historian and researcher Miika Tervonen argues that the idea of a uniform Finnish single culture is a political project that has been reinforced through the construction of the state and national identity. In reality, multiculturalism has existed in Finland throughout history and will continue to exist in the future. It is, therefore, necessary to consider multiculturalism and enabling coexistence of different groups of people also in urban planning.

How can urban planning contribute to intercultural encounters and peaceful coexistence? What is the user experience of a multicultural city, and how is this local knowledge accessed and used in planning? How is the social impact of spatial development assessed?

I studied these issues in my thesis "A diverse, intercultural city which belongs to all and where everyone's voice is heard – Tools to advance interculturalism by urban design" (Aalto University 2022). In the current political environment, these issues have not disappeared; on the contrary, they have become stronger.

Fostering multiculturalism starts with a change in mindset

In urban planning, the starting points of a planning area are often studied through physical and technical characteristics, but current methods usually neglect local social life. For example, the planning process frequently commissions studies linked to technical or environmental issues such as noise, natural features and paths for endangered flying squirrel species.

However, in what way is local social life explored or analysed in terms of how it might be affected by future urban development? Participation is legally defined as a mandatory measure as part of the planning process, but do current methods of participation genuinely reach out to residents and other users, i.e. those most affected by future changes to a place?

Throughout the thesis, the idea became increasingly clear to me that by understanding people's different realities, it is possible to design a multicultural area in such a way that it creates social sustainability and harnesses the area's potential.

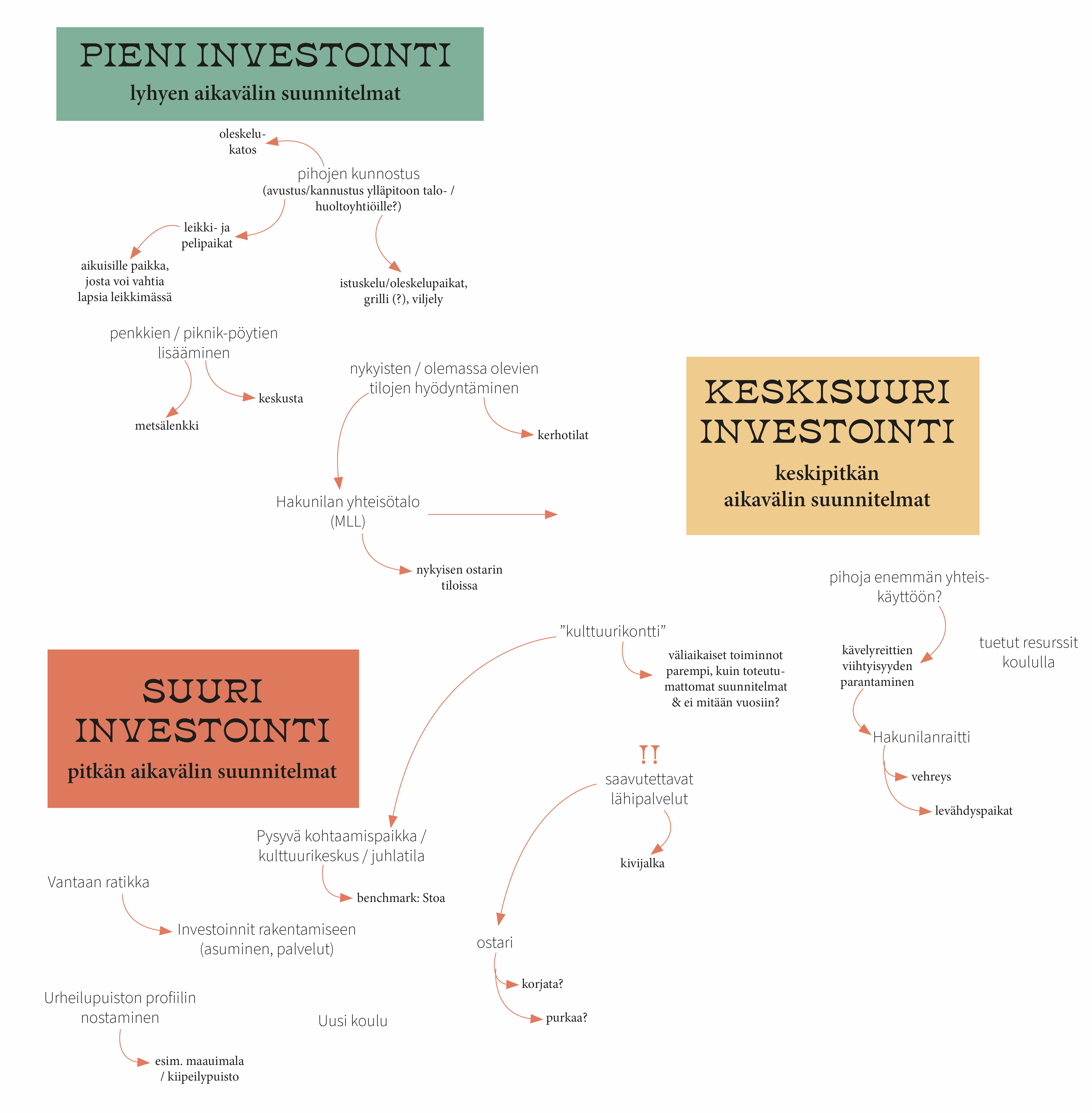

As a result, I proposed four tools to take multiculturalism and people's diverse needs stronger into account in urban planning. These are 1) a change of mindset in the city's strategy papers and values, 2) a new way of using participation, for example, through active listening and on-site involvement, 3) planning at different time levels and scales, and 4) making use of the existing resources and potential of the area.

A mindset change is a key starting point for promoting multiculturalism through urban planning, as it serves as a foundation for all other tools. A change of mindset means seeing diversity as an asset for urban development and not just as a problem. If diversity were the starting point for urban strategies and urban planning governing bodies, a multicultural city would truly be possible.

Urban development requires multidisciplinary participation

A change of mindset on inclusion is also needed. Instead of spending city and planner resources (especially time) on organising various residents' meetings and workshops, planners could go where people already are: in neighbourhood shops, community spaces, libraries, playgrounds, schools, kindergartens, restaurants, and so forth. A traditional workshop or residents' meeting may reach only certain types of people, and everyone cannot be expected to have the time or resources to play an active role in the development of their neighbourhood.

Getting the diverse voices heard requires long-term work and knowledge of the place in order to provide relevant information for planning; for example, which places are meaningful to each community. Mapping knowledge of the area could also make better use of the expertise of the city's own staff, such as community workers in residential buildings, school and nursery staff, librarians and youth workers. This would allow the existing potential of the area to be harnessed and crucial aspects of the place's identity that traditional planning methods might overlook could be preserved.

One of the tools I have presented for promoting multiculturalism in urban planning is the implementation of planning at different scales: small and short-term plans (small investments), medium and medium-term plans (medium investments), and large and long-term plans (large investments).

I argue that it is meaningful for residents and other users of the area's facilities to see that their own neighbourhood is cared for and that progress or improvements are being made also through small measures that affect their daily lives. Small and medium-scale projects do not necessarily require large investments. Still, small investments and, for example, various experiments in the area can create a virtuous circle with a positive economic impact.

Finland has also woken up to the challenges of segregation

Among large-scale projects, one tool for developing a multicultural city, especially in terms of social mixing and preventing segregation, is improved public transport connections and the resulting increase in the area's attractiveness. In recent years, Finland has woken up to the challenges of urban segregation, such as school segregation.

However, as Venla Bernelius, associate professor of urban geography, acknowledges in an interview, cities have limited possibilities to address this segregation trend. The most effective way to prevent segregation would be to tackle its roots, the structures that create inequality and poverty in society. Another key solution would be to guarantee immigrants' access to the Finnish labour market, which could break the cycle of concentrating immigrants in the city only in those areas where the most affordable housing is available.

A recent editorial in Helsingin Sanomat daily paper described the segregation of schools and stated that the measure of success of a Finnish school should be the success of all, not just the best: "A school cannot be a driver of development unless it is for everyone. It is also essential for Finnish society to have places where all of us who are different are together."

School is clearly a place where people from different backgrounds meet. However, places of encounter can also be created elsewhere: urban planning and architecture can create places that enable – or restrict – peaceful coexistence. In the current political climate of polarised social debate, the role of urban design in allowing different groups of people to live together is growing.

Emma Savela is an architect interested in the social and societal dimensions of urban planning and architecture, understanding the needs of different people and inclusive urban design. She has explored these themes in her thesis at Aalto University and in her expert work for the City of Vantaa in a project funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture to develop an approach to prevent school segregation. Savela is part of the You Tell Me collective. For more information:

www.yhteinenkoulu.fi and emma.savela(at)vantaa.fi.

Everyone’s Architecture essay series dives into the social debate around architecture. We need diverse perspectives on how architecture can strengthen both people’s well-being and environmental sustainability. Socially, ecologically and culturally sustainable architecture is based on an active discussion about how society and the living environment should be constructed. The series presents perspectives on the various themes of Finland’s architectural policy programme 2022-2035. An open-minded discussion is encouraged. The series has been realised in cooperation with the You Tell Me collective of young architects. The goal of the collective is to promote a change in thinking within the construction sector through peer-to-peer learning and sharing information, and by expanding the discussion on architecture beyond professionals in the field.