Emma Ahtiainen studied hydropower construction and its contradictory relation to cultural heritage in her thesis

Erik Kärnä

The hydropower plants of the River Oulujoki watercourse are impressive examples of industrial architecture of the post-war reconstruction. Damming rivers gained Finland prosperity but also caused unpleasant side effects. A thesis nominated for the Wuorio Prize for Young Architects studies the changes brought by hydropower to landscapes and communities.

Rivers are significant in Finnish history. Cities and villages are mostly built on riverbanks. Rivers have made it possible to get drinking water and irrigate farmland. In addition, rivers have provided food and livelihood for many people, for example, by fishing, log driving and tar transport. Finnish rapids are also part of Finland's national landscape, and the most beautiful rapids have brought tourists from far away to admire the roaring rivers during midnight sun.

Hydropower has played a very important role in Finland’s industrial growth. The construction of hydropower has advanced industrial construction skills in Finland, and the electricity produced by the power plants has enabled Finland to grow and become one of the most developed countries in the world. Hydropower and its construction have also created many jobs and a new kind of architecture in Finland. Dams have also helped to prevent flooding.

Hydropower is a renewable and clean form of energy and one of the most important energy production methods to replace fossil energy sources. However, damming rivers causes great harm to their ecosystems and biotas. This brings us to the research questions of my thesis, “The change of cultural environment related to hydropower construction: case studies of Merikoski and Muhos hydropower plants”:

Why is the cultural heritage of hydropower plant areas such a controversial topic? How have hydropower plants changed the cultural environment? How has the identity of individuals, communities, and cities changed due to the construction of dams and hydropower plants?

I researched these topics in my work on a general level as well as with the help of case studies of hydropower plants in Oulu and Muhos.

The construction of dams has also had social consequences

The golden age of constructing electricity-producing hydropower plants began in the 20th century. Hundreds of hydroelectric power plants and dams were built in Finland, and at the same time, an equal number of rapids were lost.

In the 1960s, construction began to wane a little, and today in Finland, the discussion has shifted from the construction of dams to their removal. Some removals, for example the demolishing of the three dams of River Hiitolanjoki, have already been done to restore the river's biota and ecosystem.

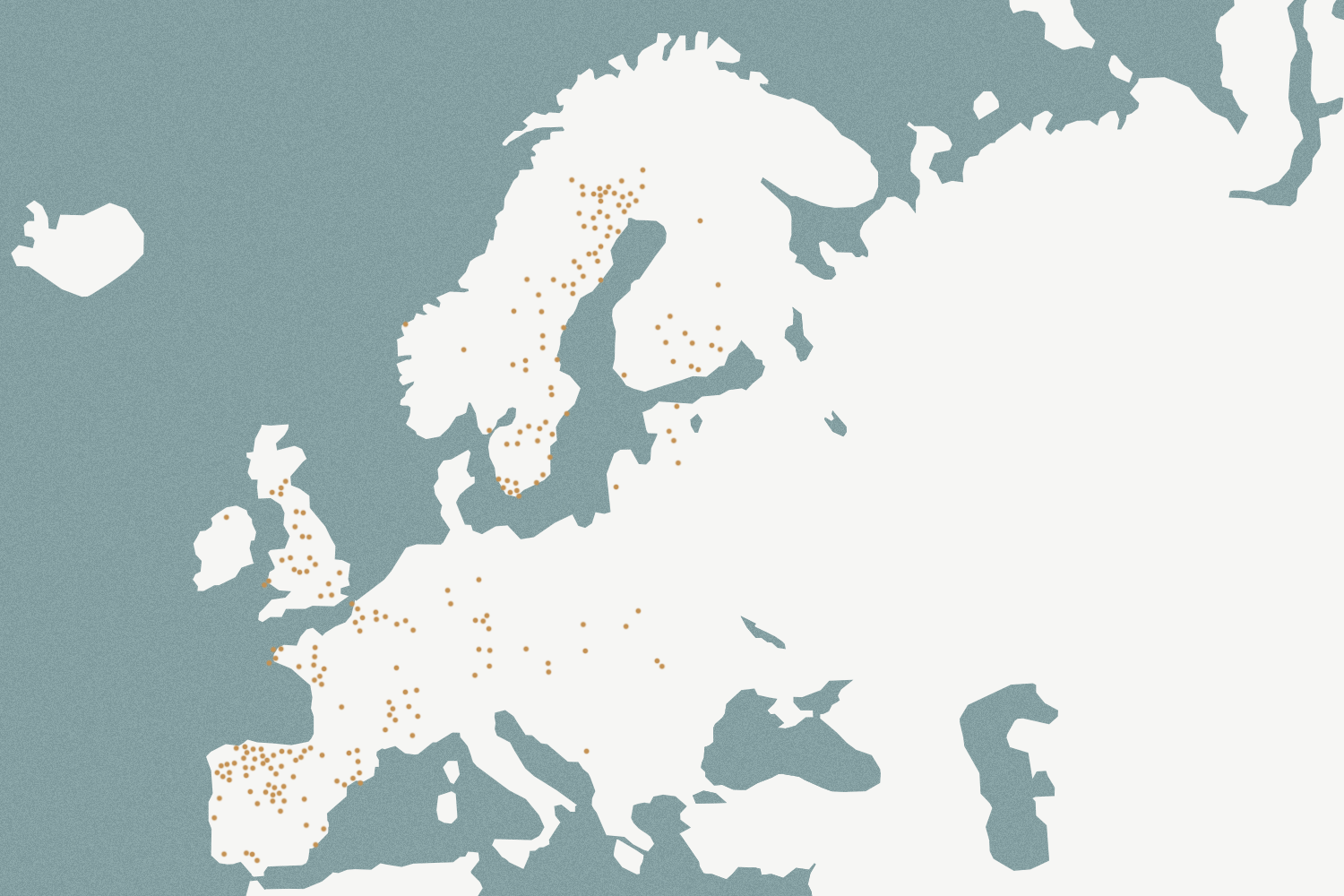

Although many dams are being removed today in developed countries, many are still being built in developing countries, for example, in the Middle East and Africa. The construction of hydropower and dams has destroyed a lot of valuable cultural environments and cultural heritage, and dams are still being built without careful consideration. Fortunately, UNESCO and other organisations are acting to prevent the construction of dams in significant cultural and natural areas.

Building dams doesn’t only affect nature and the river, but it can also have sociological effects. Docent of Sociology Outi Autti has studied the harm caused to people by sudden changes in the living environment. She calls the long-term symptoms caused by the change in the cultural environment an environmental trauma.

Autti points out that the sociological problems caused by dams have been kept quiet for decades, and only in recent years have they started to be brought up in the social debate. Research interviews show many people’s great sadness and despair, when livelihoods, familiar landscapes, and the environment experienced with many senses have been destroyed and lost.

Environments shaped by hydropower are part of the present identity

For these reasons, loss and grief have also been felt in Oulu and Muhos, both situated along River Oulujoki, albeit very different in many respects. Oulu has a long history as one of Finland’s major cities, whereas Muonio is a small rural municipality in terms of population. In both locations, however, the environmental and social changes caused by hydropower have been very similar.

In both case studies, it became clear that the riverside residents have had similar thoughts about the loss of the rapids. In both Oulu and Muhos, some residents had mourned the river’s fate, but many had also appreciated the benefits the power plants brought.

In the case of River Oulujoki, the values of natural beauty have been considered in the construction of power plants. Oulu's Koskikeskus area comprising the colourful houses on the Toivoniemi island are among Oulu's landmarks and apartments there are particularly sought after even today. In Muhos, the Leppiniemi residential area designed by Aarne Ervi is a distinguished attraction. It is a beautiful example of a functionalist, carefully thought-out residential area built in the midst of the wilderness. The Oulujoki River estuary is evaluated as a cultural heritage site of national significance in Muhos and of regional significance in Oulu.

Mistakes of the past should not be repeated

In conclusion of my thesis, when discussing the building, removing or restoring of hydropower structures, each hydropower plant and its environment should be considered individually. Hydropower plants and dams affect many other things than just the physical environment, one of the most important being the river's ecosystem and biota. Man can no longer continue on the path of living at the expense of the rest of nature and other living beings, which industrialisation started.

I argue that the advantages and disadvantages of each hydropower plant should be looked at from numerous different perspectives while considering the environmental, sociological, conservational and cultural values, which should be the base of all decisions about their fate. The opinions of the local residents should also be considered, and the residents should be involved in order to avoid environmental trauma.

The hydropower plants built during the reconstruction period should be treated as representatives of their own time, as a historical layer. New uses could be planned for the decommissioned power plants, such as museums or cultural centres.

Hydropower has once been Finland’s most important energy source, and it is still among them. Hydropower’s cultural heritage value is also significant, and it should be appreciated – albeit building it has once destroyed the area’s older cultural environment. However, recognising hydropower’s cultural value does not mean that similar decisions should be made today. Man has always shaped their environment – in the future, it should only be done in a way that respects both nature and the old building stock.

Emma Ahtiainen graduated as an architect from the University of Oulu in December 2023. The master’s thesis, supervised by professor Anu Soikkeli, was conducted as part of the Interreg Aurora-funded EU project “RE-HYDRO – Rethinking Hydropower Management: Safeguarding Biodiversity while improving Climate Adaptation”, the purpose of which is to investigate the sociological, climatic, hydrological and ecological effects related to hydropower construction in a comprehensive and interdisciplinary manner. Currently, Ahtiainen works in Helsinki at Jada Architects on renovation and other projects.

“By my work and all that I do, I want to influence and make a better tomorrow. I would like that, in the future, construction would aim to achieve harmony of the built and natural environment and that construction would no longer take place only on human terms. This we can no longer afford.”

Read more about the River Oulujoki watercourse power plants in the Finnish Architecture Navigator.

Read an article about the cultural heritage of hydropower on Archinfo’s site.