Drawing a map of political architecture

Pihla Kuusela

In the field of architecture, a strong paradigm shift can be seen, and the role of the architect can no longer be perceived in the same way. This political and ever-changing landscape of architecture is addressed by Pihla Kuusela in her text for the Everyone's Architecture series.

Architecture is about re-imagining and envisioning not only the unbuilt but also the society that we live in. Each new plan or idea can be seen as a proposal for an imagined future that challenges prevailing social norms and creates space for a new way of thinking, challenging the hegemony of the present.

Therefore, architecture does not only follow political discussion but actively produces a political realm by defining over and over what change (for the better) means.

Architecture is political because architecture unavoidably engages with societal structures. Since architecture cannot be separated from its social context, it continuously reconfigures power relations, influencing how society is structured.

However, it must be recognized that radical architectural forms do not directly translate into radical politics and vice versa. To foster the concept of building a better future, understanding architecture's political landscape is crucial.

The return of the political

During the economic crisis of 2008, architectural discourse shifted towards greater political engagement. The widespread socio-political implications of corrective measures during the challenging financial situation seem to have reignited interest in the socio-political conditions that also influence the architectural discipline. Viewing architecture merely as a physical product no longer provides us with sufficient tools to tackle modern issues.

Today, architecture is increasingly seen as a continuous process which are characterized by community engagement, participatory practices, and responsiveness to socio-political issues.

Nevertheless, architect and professor Jeremy Till still argues for fundamental changes in how we perceive architecture. Rather than sticking to the current paradigm of problem-solving and constructing solutions, Till advocates embracing agency to empower and recognize non-architects in exploring new possibilities in the field.

In this context, a pertinent question arises: what role do architects play if building solutions are no longer at the core of the profession?

The changing role of architects

As we all know, traditionally architects have often been portrayed as exceptional individuals. To tackle current pressing issues, architects must be prepared to expand their role beyond traditional boundaries.

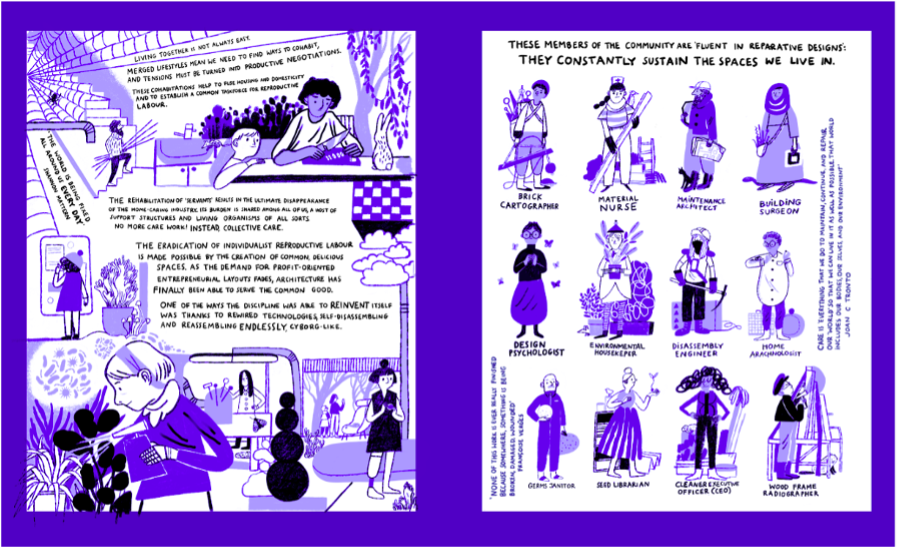

One approach that many have adopted is envisioning a new future for architects. For instance, in their utopian graphic novel "Architecture Without Extraction," Zosia Dzierzawska and Charlotte Malterre-Barthes introduce entirely new professional roles for architects. In their future scenario, architects' primary task is no longer focused solely on designing something new. These new professional roles include maintenance architects, building surgeons, and design psychologists.

On the other hand, the topic can be viewed through the lens of what remains when new buildings no longer dominate the professional identity. Discussions are increasingly highlighting soft values and a human-centred approach to architects' work.

For instance, the concept of care, which has gained significant attention recently, is closely linked to inevitable shifts in the architect's role and responsibilities. Striving for sustainability and inclusivity, Lacaton & Vassal's philosophy centres on respecting existing structures. Instead of demolition and reconstruction, they advocate for the adaptive reuse of buildings, promoting minimal intervention and maximum enhancement.

Furthermore, as architects extend their roles beyond traditional boundaries, many are embracing activism more than ever before.

Architects = activists

The political dimension of architecture appears to be increasingly intertwined with activism and "alternative architectural practices," as described by Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. The emergence of architectural activism, emphasizing collaboration, provides an opportunity to reimagine the practises in the field of architecture.

This paradigm shift entails viewing architecture not merely as a supplier of functionality and aesthetics, but also as a mode of activism—a political endeavour. Architect and researcher Natalie Donat-Cattin explores this transformation in her writings:

This emerging generation of architects and non-, thanks to its public focus, social agenda, and ecological preoccupations, suggests alternative ways to critically read the built environment or imagine the un-built.

Recently, these collective processes embodying activism have materialized through architectural collectives and similar collaborative initiatives advocating for paradigm shifts, often linked to the resurgence of environmental activism.

Within collective work, the current paradigm is portrayed in a more holistic manner than traditionally perceived: it is not merely academic or theoretical. Instead, architectural theory is intricately intertwined with real-world challenges and opportunities, influencing the trajectory of our built environment and society at large.

Architectures’ political landscape

In 1969 Architect Charles Jencks's draw a map of the predicted future, Evolutionary Tree to the Year 2000. Based on the previous historical context and current climate back in 60’s, Jencks attempted to predict the future of architecture up until the year of 2000. This speculative but also analytical endeavour has drawn significant attention and participation from various architectural circles, and intrigued architects to the date.

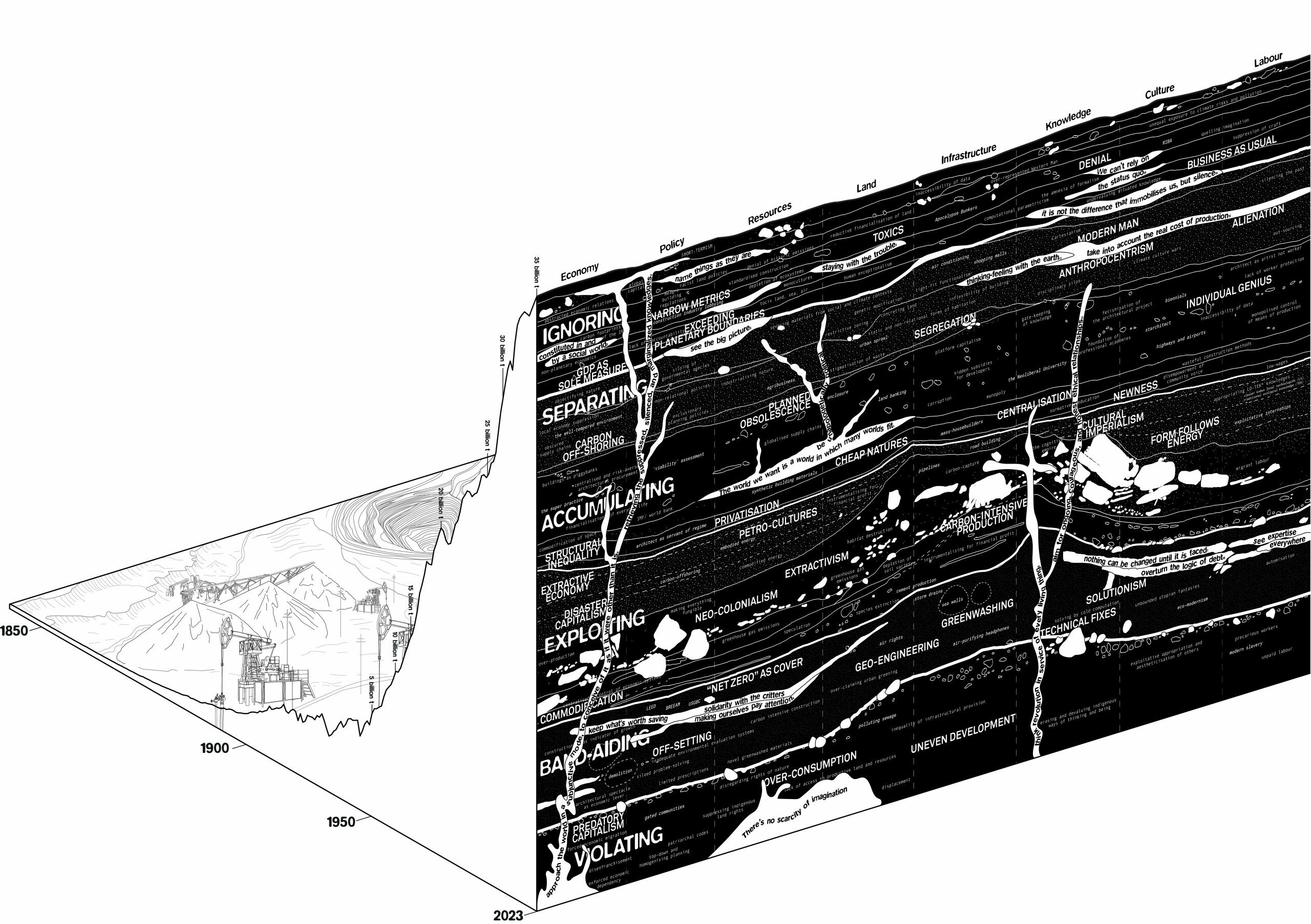

Last year, 2023, e-flux Architecture and the Jencks Foundation collaborated in the project titled ‘Isms and ‘Wasms: Chronograms of Architecture, a project aiming to chart and visually represent the intricate intersections of architecture and current architectural climate.

For example, MOULD -collective created their version of the Jencks diagram called Architecture is climate. The work suggests that architecture and climate are mutually constitutive conditions It promotes practices that cultivate alternative material and socio-cultural arrangements and urges architects to actively participate in activism, politics, and education to reform societal dynamics and develop architectures that can effectively respond and adapt to evolving climates.

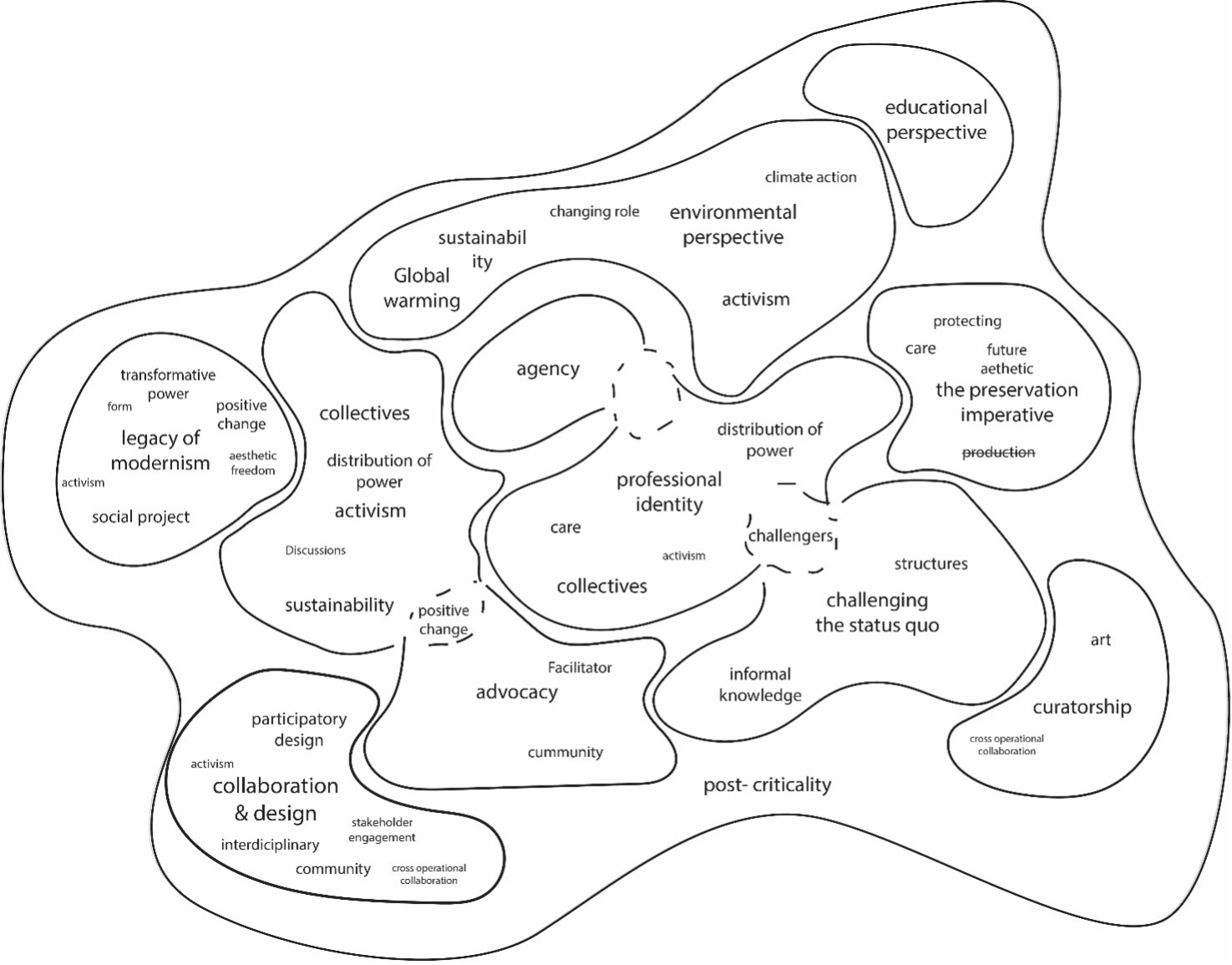

Inspired by these endeavours I have drafted my interpretation of this famous diagram presenting the current political landscape of architecture in which I situate the current political paradigm within post-criticality. When examining the current political landscape of architecture, it becomes clear that theory and practice are not separate from one another. The landscape is deeply intertwined with real-world challenges and opportunities, shaping the trajectory of our built environment and society at large. It is deeply intertwined with real-world challenges and opportunities, shaping the trajectory of our built environment and society at large.

As the diagram reveals, the current theoretical paradigm post-criticality manifests political dimensions in various ways, even though post-criticality is often perceived as apolitical. Today's post-critical discourse encourages architects to engage directly with political realities, urging them to critically assess their societal impact. It emphasizes operating within lifeworld contexts, emphasizing a deep understanding of the socio-cultural, economic, and environmental landscapes that shape architectural interventions. This discourse highlights architecture's potential to drive meaningful change.

Pihla Kuusela is an architect. Her master's thesis "Architecture's political landscape - Exploring architecture's 'political' through a post-critical lens", completed at Aalto University in 2024, deals with the politicisation of architecture from several different perspectives.

Everyone’s Architecture essay series dives into the social debate around architecture. We need diverse perspectives on how architecture can strengthen both people’s well-being and environmental sustainability. Socially, ecologically and culturally sustainable architecture is based on an active discussion about how society and the living environment should be constructed. The series presents perspectives on the various themes of Finland’s architectural policy programme 2022-2035. An open-minded discussion is encouraged. The series has been realised in cooperation with the You Tell Me collective of young architects. The goal of the collective is to promote a change in thinking within the construction sector through peer-to-peer learning and sharing information, and by expanding the discussion on architecture beyond professionals in the field.